A mid-size show, the Jakarta Biennale could easily be seen in one day. It was held between the 15th of November, 2015 and the 17th of January, 2016.

The Jakarta biennale was a hard show not to like. It did well what other biennales do badly. A common flaw among biennales, a flaw that tends to limit their ability to represent local concerns, is that they are almost exclusively peopled by artists and curators foreign to their host countries. And though the Jakarta biennale did have a renowned foreign head curator, Charles Esche, and important foreign artists, including Superflex and Renzo Martin, it was largely populated by local artists and curators. Apart from Esche, all of the show’s curators were Indonesian and each was from a different province; additionally, all benefitted from the fact that the show functioned as a lab, created to develop the country’s stock of curators. Along with the majority of the curators being Indonesian, an exceptionally large number of the biennale’s artists were also Indonesian, from all over the country. Additionally, most of the non-Indonesian artists came from the region.

Another common flaw among biennales is that most are apolitical—this in spite of conceiving of themselves as highly political affairs. And even if they are political, most biennales avoid showing works whose politics might challenge local norms or élites, and often any politics that are included are tempered with a sort of cynicism. In contrast, the work in the Jakarta Biennale was extremely political, created to address local audiences, and was upbeat; so upbeat, in fact, that Renzo Martin’s brutal, often funny and deeply cynical film Enjoy Poverty, seemed completely out of place there.

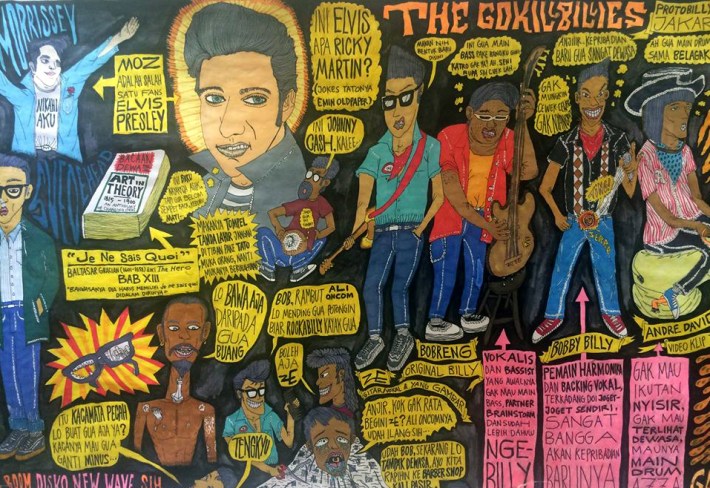

History and memory were important themes at the Jakarta Biennale; they were often used by Indonesian artists to look at local history. One example of this was Bron Zelani’s Act Like A Man, a large colorful drawing in the style of a comic book. It chronologically follows the history of rockabilly in Indonesia, starting with the internationally renowned Indonesian rockabilly group the Tielman Brothers. Another example was Idrus bin Harun’s very political mural Bhaneka Tinggal Luka. Harun’s style was vaguely reminiscent of the work of Jose Clemente Orozco, and his mural documented the negative effects that oil exploitation as well as conservative religious and military leadership have had on the country. Additionally, the work’s title was a complex wordplay wherein Indonesia’s official motto “unity in diversity” was slightly modified to read as “dolls left with wounds.”

Ariani Darmawan’s film Sugiharti Halim (Click on the title to see the film online) was a third example of a local artist making work about Indonesian history. This fictional film took as its starting point an historical event, the 1966 Presidential Decree no.12/U/kep/12/1966, which forced those Indonesians with Chinese-sounding names to change them to Indonesian-sounding names. Set in contemporary Indonesia, the film shows a woman on a series of failed first dates complaining about the effect that the law has had on her and her name. This subtle, funny little film was able to tease out the political implications of the decree.

The video installation, Towards figures of dedication, and a flood, was perhaps the most important work in the show. It was created by Tom Nicholson, a non-Indonesian artist, with the help of Grace Samboh, an Indonesian curator. The work is about Indonesian history and the construction of memory. In the video, Nicholson and Samboh interview Edhi Sunarso, an important Indonesian sculptor known for having created some of the country’s most important monuments. He was commissioned to create many of the country’s historical dioramas. The video explores the production of these dioramas, which were created to construct official memory. As opposed to seeing history as a transparent key to understanding the present, Towards figures of dedication, and a flood looks at how history is often constructed and instrumentalized by the powerful. (Click here for an English transcript of the video).

Another important work made by a non-Indonesian artist that touched on Indonesian history was Jeremy Millar’s beautiful and meandering essay film Adbo Rinbo (Je est un Autre) (Click on the title to see the film online), which takes as its starting point the history of Arthur Rimbaud’s visit to Indonesia. The film follows some of Rimbaud’s own meanderings, but also touches on Gustave Courbet’s role in the destruction of the Vendome Column.

Oscar Muñoz had two small beautiful videos that functioned as metaphors of memory and forgetting. They were also connected to one of the biennale’s other important themes, water. In Dystopia, a video showed pages with text being dipped into a solvent which dissolved the text into individual letters; the letters rotated in different directions, clumping together into unintelligible patterns of lost meaning. In a similar fashion, Muñoz’s video Ciclope showed photographs dissolving in a whirlpool of solvent, the photographs’ detached blacks and grays pooling in amorphous bodies of an irretrievable past. Muñoz’s use of water connected his work to much of the other work in the show. Water was a perfect theme for an archipelago like Indonesia.

Another example of an artist working with water was Dea Widya, whose wonderful work, A City of Anywhere was critical of the universalist claims of modernist architecture. Widya created models of modern buildings out of dried clay, and placed the buildings in hidden pools of water. Over the course of the show, the models absorbed water, and one by one fell apart. Widya used water to stage the failure of modern architecture to adapt to the particularity of Indonesia as a site.

Many of the other works that dealt with water touched on the environment and the coming environmental crisis. Tata Salina’s playfully incisive project 1001st Island-The Most Sustainable Island in Archipelago (Click on the title to see the film online) was an example of this. Salina was doubtful about the viability of Jakarta’s land reclamation project that aims to create new manmade islands. This land reclamation project not only is likely to negatively effect fishermen, forcing them to go further out to sea to make their catch, but also does not seem to achieve its stated goal of creating new housing for the poor to offset the land lost in Jakarta as the city sinks; most of the space created by the land reclamation is reportedly set aside for luxury housing and golf courses. (Click for an article on the subject.) So, with the help of local fishermen, Salina created a new island made out of the trash that people have thrown in the water. Salina’s work suggests that polluting is man’s most viable project. Her film ends with a beautiful aerial shot of the artist standing on the island as it floats out into the ocean. The show’s concentration on upbeat political work that addressed local audiences made the Jakarta Biennale a very enjoyable show.

©Vincent Pruden