The Bucharest Biennial was a small show that was seeable in a long afternoon. It was curated by Beral Madra and Răzvan Ion and was up from May 17th to July 8th, 2018.

Jetlag seems to have become my alibi for insomnia, a way of excusing the fact that my body has truly absorbed the rhythm of the reality TV show that has become our political life. At first when I traveled I would only be awakened by late Friday afternoon’s (EST) news dump, revelations, or firings. Now my body monitors the news all the time, it is on edge for the early morning tweets, the market’s reactions, the press briefings, and the late-night comedy shows. Attuned to the performances’ rhythm, my body cues me when it is time to scan the newspapers, read the blogs, and watch cable news. On Sunday, I awoke bewildered not because my Bucharest hotel room was unfamiliar, but because it was time to be engrossed with the news cycle’s current drama, child removal.

The Bucharest Biennial was a diminutive show housed in two small galleries and one cultural center. It was so small that it was easy to leave with a collection of the show’s principal works, a series of posters, stuffed in a carry-on bag. It was so small that the whole show could have fit six times over in Blum and Poe’s LA space, eight times if you also installed work in the office. Its significance lay not in its size or in what it did, but in what the show set out to do. The biennial’s focus was on how art can address our post-truth world.

The biennial asked each of the show’s artists to create a poster. The posters were arranged in neat piles in the exhibition space, given out to visitors, and each was exhibited alongside an earlier work that had inspired the artist. The artists mostly used the posters to help unpack these earlier works. The one exception to this was Anna Khodorkovskaya, whose poster read “Marx Lenin Pig” and was a reaction to Animal Farm. A copy of Orwell’s book hung from a thread in the gallery space. This reference to Animal Farm was an indication of the show’s reliance on older models of propaganda.

All of the posters, except for Anur Hadžiomerspahiç’s design work and Liviu Bulea’s About White, carried less punch then the earlier works that had inspired them. Hadžiomerspahiç was a well-known designer whose work functioned as a sort of counter-propaganda. He died in 2017 and the biennial showed a couple of his political designs. The one used for the poster criticized the use of religion to bolster political power, the other engaged those who profit from war, showing an egg carton filled with hand grenades, and reading “Buy Five Get One Free.”

Bulea’s About White fit into one of the show’s main focuses, artists who engage our post-truth world by seeking the truth. His poster looked at the crowded space and dilapidated state of Romania’s private and public hospitals. To produce his poster, Bulea asked people on social media to send him photographs of the country’s hospitals. His poster contained a collection of these photographs. They were meant to evoke the memories that people had of these institutions. The collection of photographs suggested that a bad experience at one was similar to the experience one would have at the country’s other institutions, thus transforming one’s personal experiences into knowledge about the whole system. In the same space was the work that had inspired the poster, a white tile wall which Bulea had removed from one of Bucharest’s hospitals. This was a good example of an artist using the poster to help unpack an earlier project.

Other artists also sought the truth, with a number of artists focusing on borders. Mkrtich Tonoyan showed the film A Little War a Little Peace (click to see a version of the film online) that Tonoyan produced, and which was directed by Arman Yereitsyan. The film looked at the stewing conflict between the Republic of Armenia and Azerbaijan, with Azerbaijani snipers shooting across the Armenian border. The director interviewed Armenian villagers who were forced to endure these attacks. On the poster, Tonoyan asserted that a safe home is a basic right. In the film these events are framed in terms of the different articles of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, grounding them within these international conventions.

Ana Riaboshenko’s small work, ACHTUNG! POZOR! UWAGA! and poster also invoked international relations. The work’s title referred to the German, Polish and Czech versions of a caution sign, and looked at the European Community’s failure to fully integrate itself. In the poster, Riaboshenko pointed to a bridge that connects Germany, Poland and the Czech Republic. On the Czech and Polish sides, signs celebrated the union. But on the German side the bridge was blocked off.

The Bucharest Biennial touched on a number of subjects that are critical to understanding the role that biennials play. Riaboshenko’s project on Europe’s failure to completely integrate itself, Tonoyan’s invocation of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, the Bucharest Biennial’s own insistence on its role as a civil society organization, and even the fact that all of the show’s works were in English (without Romanian translations) pointed to the Bucharest Biennial’s relationship to globalization, and to our fear that biennials in general function as boosters for neoliberalism. Whether they do or not is a real question, and deserves a treatment far beyond the scope of this post. Yet it is hard not to see the Bucharest Biennial in relationship to Eastern Europe’s particular political conditions, with civil society and European integration as elements that have helped to bolster these countries democratic institutions.

For the Bucharest Biennial, Naeem Mohaiemen slightly modified his film Der Weisse Engel. Along with the poster he created for the show, these changes were meant to point to the way the film fit into Mohaimen’s larger body of work, where the artist often integrates his own experiences or his families into a historical account. This tends to give the work a pleasing openness, encouraging viewers to question the work’s truth claims. But Der Weisse Engel’s connection to the artist was never straightforward, and in the context of The Bucharest Biennial with its focus on our post-truth world, even the extra emphasis that the artist placed on this connection had little effect. Instead, the film seemed to point to the way that reality can be more complex, more unpredictable than fiction. Its effect was like a realist novel. Der Weisse Engel examined the modest film career of Lotte Palfi Ardor, a German Jewish actress, and the way that her only roles in important films turned around World War II and diamonds. In Casablanca, she played a woman selling her jewelry. In the Marathon Man, set in the 1970s, she was a survivor of the death camps who encountered one of her tormentors in New York’s diamond district. In real life, the actress fled Germany in 1933 and refused to return to this homeland even though it meant being left behind by her husband. The film fit into the show’s larger questions about truth, taking on our simplistic narratives about history, and seducing us with the allure of the unpredictable, the coincidental, and with the image of reality as fundamentally unresolved.

Questions about homeland appeared in a number of different ways in the show. Both Der Weisse Engel and Tonoyan’s A Little Peace, a Little War pointed to the possibility that a homeland could be hostile, with A Little War, a Little Peace asking what it would take to motivate someone to leave their homeland and become a refugee. The show also included Bogdan Rata’s sculpture, The Crossing. It was installed in the Dâmbovița River and performed the stereotypical role of the refugee making the crossing.

Nándor Angstenberger’s drawing Karosmetic took on the attributes the artist associated with homeland. In his poster he described these attributes as “stability, structure, and strength.” His abstract work, which was both horizontally and vertically symmetrical, offered viewers the kind of stability that we associate with certain types of modern art. Interestingly, at the Bucharest Biennial it appeared to offer viewers a sort of rootedness, compensating for the malaise created by our post-truth world.

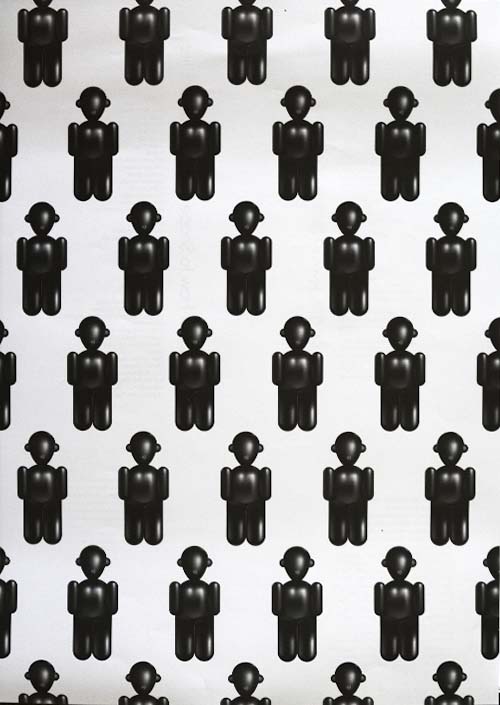

And though it is hard to say that we have lost our homelands, our post-truth world seems to challenge our sense of ourselves as inhabiting nations; this, in spite of having inspired forms of extreme nationalism. The truths, or at least the certainties that we have shared together seem to have disappeared. This is surely why so many of the show’s projects focused on establishing truth. They seemed to want to cross over the boundaries that propaganda creates. They wanted to re-establish a shared truth, to connect with fellow citizens, whom we no longer seem to know. Martin Balint’s work, Blo500 or How to Shape Undisclosed Identities, seemed to explore our desire to know the people that we share a nation with, those people in our imagined communities. The work invited viewers to blow up small inflatable black dolls and place them anywhere in the space. The dolls were identical to each other. In a sense, they came to represent the viewer who inflated them. In the space, a voiceover recited what seemed to be the possible identity of each, starting with “a gang of protesters,” and including entries like “human-imitating bots.” And so, we found ourselves fantasizing about who is represented by each, in the same way as in our divided societies we struggle to imagine those people on the other side of the political divide.

The Bucharest Biennial was an important show. Unfortunately, it seemed to examine older forms of our spectacle culture. In the last couple of years, the spectacle’s rhythm and intensity have increased. We find ourselves more and more compelled to watch. And our humanity, our righteous anger, have now become tools to divide us. If art is going to take on this post-truth world, it needs to understand these changes.

©Vincent Pruden